ALAIN GOMIS

REWIND AND PLAY (Grasshopper/Ina/Andolfi/Sphere Films)

Josephine Baker made a huge splash in France, first as a semi-nude cabaret artist in the 1930s, then as a resistance fighter in World War II, then by adopting scores of orphans after the war. She became a hero, and is the only black American woman buried in the Pantheon in Paris. Lots of black American writers, James Baldwin and Chester Himes to name two, and jazz musicians, Dexter Gordon and Miles Davis, for example, spent time performing there. Some moved to Paris because it was hip, sophisticated and not racist — we thought. But this new documentary about Thelonious Monk raises some serious and depressingly familiar issues. Monk was there to perform in 1969. It was his eighth trip: he was tired, ill and frustrated with Colombia Records' attempt to market him to a rock audience. Then he spent the entire day before his evening concert in a television studio under burning lights with a terrible entitled host asking lame questions; Monk having to endure endless takes, while they got the guy posed right ("both elbows on the piano now!") or shot closeups of Monk's beard, or his nose and eyes. This is the raw footage from a TV show called "Jazz Portrait" which was abandoned. It's a real hodge-podge, and while we love seeing color footage of Monk, it has not been presented well. The first 15 minutes are home movies of Monk and Nellie arriving at the airport, taking a limo to the hotel while chain smoking, getting out of the limo. Then Monk is in a bar, having a couple of brandies while a white guy (his manager?) eats a boiled egg and says, "You can't get this at home." What? boiled eggs? asks Monk. No, free food in a bar, the guy says, stuffing his face. Then a woman comes over with a little grey poodle, "Cute doggie," says Monk petting the animal while a voice off, says in French, Your dog has pissed over here! It's all quite banal, would require Peter Sellers to make it amusing. Monk lights another cigarette, rewind, he gets out of the limo again. Pointless as it is, there is also a big flyspeck on the lens throughout this footage. How hard would it have been to clean it digitally, or get rid of the blank leader and burned out bits of film from the end of the reel which pop up periodically to point out the amateur nature? Then we get to the studio and a completely disorganized shoot, with Henri Renaud, the "White French Guy" announcer asking "Why do you have a piano in your kitchen?" He seems to think this is profound and wants Monk to say more than, It is the biggest room in the house. Well, there it is between the gas stove and the sink, next to the ironing board, the WFG says. The guy asked, Who is Nellie? — My wife and mother of my children. WFG turns to the camera and explains, in French, Nellie and Monk met as youngsters and have been inseparable since. She tells him what to do, arranges everything. Then he asks Monk why he was unknown for so long, again turning to the camera to explain how Minton's jazz club in Harlem where Monk played every night with the likes of Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, was "the Bauhaus of jazz." Of course he has to say everything three times as he constantly screws up. "Merde!" Finally we get to hear bits of Monk playing, though at one point the tune is jerked forward as if the cameraman got bored and hit pause a few times. Monk, it seems, is just an excuse for the WFG announcer to prattle on about jazz and how Monk was too avant-garde for French audiences in the 50s. No, says Monk, I was on the cover of the program. Sure Gerry Mulligan played, but I was the star. However, I got the least pay! You can't say that, says the WFG, it's not nice. But it is true, says Monk. Renaud repeats the question and gets basically the same answer. Monk is frustrated, pours a brandy. You can tell he wants to leave, finally we get uninterrupted shots of him playing "Crepuscule with Nellie," Don't blame Me" and he gets up to go. We need one more, medium tempo... say the WFG. One more, then I can go? Yes. So he rips into "Nice work if you can get it," full stride fashion, with lots of whole-tone glissandos and trinkly high notes. This is a poor excuse for a documentary. Some interviews could have provided context. Black men in white society are treated as pets or threats, this is what should be addressed and why someone of Monk's stature was constantly treated like an idiot savant.

THELONIOUS MONK QUARTET

PALO ALTO (Impulse/Legacy)

It seems that about once every year or so a previously undiscovered album by one of the jazz greats, such as Monk or Coltrane, comes to light. I gave up being a Monk completist after the rediscovered soundtrack to Les Liaisons Dangereuses surfaced. It was so hyped in advance: an actual film soundtrack! wow, this might be up there with Elevator to the Gallows by Miles Davis, but then it was just Monk rehearsing a standard set, and a huge let-down. So I passed on the weirdly spelled Mønk, and held off on the Coltrane Blue World. But then the latter turned out to be fantastic, and now this newly discovered Monk Palo Alto high school gig from 1968 is also a formerly lost gem.

But don't expect anything startlingly new. It was a good night: Monk is in fine form. I can't believe this is the whole show -- it's been honed down to 47 minutes of essential Monk -- four tunes plus his outtro music "Epistrophy" and a coda. In his career, starting with Coleman Hawkins in the 40s, Monk accompanied the finest tenor saxophone players of the post-War era, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, both of whom grew in his band. But mostly he was accompanied by Charlie Rouse, who fits the bill perfectly. Rouse doesn't showboat, he understands the music, he plays relatively straightforward solos, reading the charts, and lets Monk do the far-out stuff.

In 1968 Monk's career was winding down. His label, Columbia were not happy that he kept re-recording his own tunes, wanted him to try the Beatles songbook to spice things up. "Eleanor Rigby"? Maybe, "Yellow submarine"? No way. Actually I have massive respect for Monk as a recording artist: he wrote about 60 tunes and while he did record them over and over, and they formed his key repertoire, they evolved. Also, he always threw in a Tin Pan Alley song, like "Sweetheart of all my dreams," "Lulu's back in town" or "Tea for two," to show how he related to other's phrasing. This is very instructive. Furthermore, can you really see him standing next to the piano like Lee Liberace and saying, Now, for a special treat, we take you back to one of my classics, "Round Midnight"! His first two Riverside albums were all covers: the brilliant set of Duke Ellington which announced Monk with a bang, and a follow-up The Unique Thelonious Monk, which showcased Gershwin, Fats Waller, Rodgers & Hart. It would have been great to have a whole album of Harry Warren, or James P. Johnson material, but I am not complaining.

In the snippets of Teo Macero you see in the various documentary footage of Monk, the producer comes across as a buffoon who is indulging his pet bear without really trusting him. Monk's last album for Columbia, Underground, contained new music and appeared in 1968. That album won a Grammy -- for the cover art, not the content, and the cover led to the foolish notion that Monk had fought in the French Resistance during World War II. Monk did not go on a promotional tour, as you would expect, instead he went into a long depression that kept him silent for the rest of his life, with the exception of a single date at Chappell studios in London in November 1971. In 1968 in fact he had a seizure and was misdiagnosed by doctors. He missed recording dates which meant he went into debt to the label, which was why he needed to play a long stand in a friendly spot like the Jazz Workshop. He lived another 14 years but even as his fame increased, so did his isolation. Columbia filled the void and the demand for his work by issuing live gigs, such as Live in Tokyo (from 1963) the It Club, and the Jazz Workshop (1964) sets.

But he was alive and well when a kid from Palo Alto contacted his manager to see if he would play a gig at the high school. As the quartet was making a trip out for a three-week stand at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco, they thought it would work out fine. And then, as luck would have it, the old janitor was a music buff and had a recording setup (aside: my uncle worked at Ampex in Palo Alto, developing tape recording technology in the 60s). The janitor said he would tape the gig if the school got the piano tuned. Tickets were $2 but no one bought advance tickets figuring it had to be a hoax. Then on the night of the gig, the band arrived in the high school parking lot (driven down by a student, the bass sticking out the window) and there was a rush to get in and hear them. Everyone is having fun, Ben Riley and Larry Gales, the rhythm section, swing hard and this may be the last time we hear the "classic quartet" as they became known, in top gear driving form. It's the same band who freshly assembled were recorded live in LA at the It Club on Hallowe'en 1964, and the next night, and then again the following two nights in San Francisco at the Jazz Workshop in 1964, so you can compare the versions to those, if you want. Well, apart from the opener which is a lovely 7-minute take of the ballad "Ruby, my dear." One of Monk's first compositions, he wrote it for his first girlfriend when he was a teenager. There is a resounding "Well you needn't," followed by a solo "Don't blame me," which is so sharply recorded you can hear Monk's shoe on the floor adding his two-step invisible organ pedal percussion. This is a classic of his solo style: womping stride chords in the left hand and death-defying whole-tone runs in the right against a lop-sided rhythm. His sense of time was unique, imagine you are swaying from side to side and your arms are swinging unconsciously by your side, hanging loose. The audience is attentive and digging it, they applaud the bass solo by Larry Gales in "Blue Monk," then go nuts for Ben Riley's drum solo before the resolution. It's all over too quickly, and then applause flares up and down as there's a solo taste of "Sweetheart of all my dreams," which sounds like the piano is being wheeled off stage, and a final comment "We have to hurry back and get to work..."

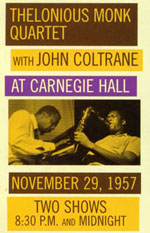

THELONIOUS MONK QUARTET WITH JOHN COLTRANE

AT CARNEGIE HALL (EMI/Blue Note 0946 3 35173 2 5)

I know this doesn't need reviewing. Anyone with any interest in jazz has already heard about it and bought it. In some ways it's sad that the most exciting jazz album of the year is a 1957 recording, but whose fault is that? The only flaw with this CD is the cover which has a lame line drawing when there's a great poster they could have used. And one presumes that this magical night of music that showed up in the vaults of the Library of Congress will eventually be released in its entirety. Each act did two sets of about 25 minutes long, so both sets make an hour of listening. The other artists were Billie Holiday, Ray Charles, Dizzie Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, & Chet Baker with Zoot Sims. What a night!! This is essential listening because the only other live recording of Monk and Coltrane is so dire. In fact it was taken off the market and then remastered at a different speed! There are no sonic problems here though it seems as though there was one mike at the front of the stage so you get lots of Coltrane and Monk and only a bit of Shadow Wilson on drums and Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass. It's a lovely hour of two geniuses having a good time. Right from the start "Monk's Mood" is just the two of them shadow-boxing till Shadow Wilson gently taps at the door with his brushes on the snare. The first set consists of some of the songs recorded by Monk with Coltrane: "Monk's Mood," "Nutty," "Crepuscule with Nelly." Monk is really dancing on the ivories when Trane locks in. But the midnight set includes tunes by these men not previously caught on disc. It starts with the Latin tinged "Bye-ya," followed by "Sweet & Lovely" and "Blue Monk." "Sweet & Lovely" starts at its usual relaxed pace, then when Coltrane enters it goes into a rave-up before cooling down again. The tape runs out during the final version of Monk's perennial outro number, "Epistrophy," and for the first time ever I was sorry to hear it end abruptly because the two titans were getting into a groove on this jerkiest of ditties. Coltrane of course could rage on "Twinkle twinkle little star" if need be. It's really apparent that his stint with Monk brought his art to perfection and he is in fine form on this night questing and exploring and pushing the often reticent Monk into more bravado than you hear with other tenor encounters.

THE LATIN SIDE OF THELONIOUS MONK

Liner notes for an unrealised album

Thelonious Monk is remembered as one of the greatest American composers and performers of the twentieth century, alongside George Gershwin and Duke Ellington. But unlike those two legends, Monk's tunes are not so familiarly engrained in the popular consciousness. This is partly because many of them owe their appeal to the eccentric original performances of the composer. It would be pointless to try to emulate Monk's style, so his oeuvre remains whole and separate from the evolutionary process that affects the work of other composers as interpretations and arrangements evolve. Monk was never happy with others' versions of his tunes. (Not surprising, since "Round Midnight" is most often played in the "wrong" Miles Davis arrangement.) Monk fans tend to collect his performances despite the narrowness of the repertoire, aware that there is great richness in each variation.

It's a known fact that when Monk first got together with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker to pioneer what became known as Be-bop music they deliberately wrote complex changes in order to shake off rubes who would attempt to sit in with them. The only way to forge a new music, they felt, was to demand genius and bravura performances. The result was a revolution in American music. The complexity and sophistication of Monk's tunes belies the underlying simplicity of many of them. His distinctive sound is a result of harmonic shifts as many of the compositions use parallel seconds ("Epistrophy") or thirds ("Blue Monk"), giving them that distinctive Monk sound. Monk used well-known tunes as the skeletal structure for his own pieces: "Honeysuckle Rose" was the bridge for both "Let's Cool One" and "52nd Street Theme." "I Got Rhythm" was deconstructed in "Rhythm-n-ing" (his first composition, dating from 1941), "Humph," and also "Little Rootie Tootie." Among the many old Tin Pan Alley songs played by Monk was the 1929 "Just You, Just Me," which he made peculiarly his own by exaggerating the bass and emphasising the quirky short melody and little twists and turns. According to Charley Gerrard he used it as the basis of the even quirkier "Evidence." But in general, like other Be-bop artists, Monk simply used the chord progression and wrote new melodies over the changes. Hence we have "Sweet Sue" transformed into "Let's Call This," "Sweet Georgia Brown" becomes "Bright Mississippi," and Gershwin's "Oh, Lady be Good!" becomes "Hackensack."

|

|

Songs like "There's danger in your eyes, Cherie!" from "Puttin' on the Ritz" and (the usually mis-identified) "Sweetheart of all my dreams" from MGM's "Thirty seconds over Tokyo" didn't take much to become Monk classics. There's already lots of the "grit" and "speckled noise" that we associate with his style in the little internal grace notes and fills put there by Richman, Meskill and Wendling, or Fitch, Fitch and Lowe.

Predictably, after Monk's death in 1982, tributes to his work appeared. The most ambitious project was a double album called "That's the Way I Feel Now" which succeeding in demonstrating how Monk's tunes could be perverted by bad rock guitar into speed-metal blazes, among other ignominies. The only insightful selection on the entire double album, arguably, was Randy Weston's version of "Functional," a straightforward homage.

Latin jazz has deep roots. Louis Moreau Gottschalk's compositions paved the way for much modern North American music. He was in Puerto Rico in 1857 picking up on the habanera rhythm. Two years later in Cuba he met Manuel Saumell, father of the Cuban contradanza. Gottschalk wrote "Souvenir de la Havana" in 1859, expanding on the musical idea of the habanera and doubtless influencing Bizet whose "Carmen" famously used the same rhythm a decade later. What Jelly Roll Morton called the "Spanish tinge" comes out of the same New Orleans blend of Congo and Creole influences as Gottschalk's Ur-"Latin jazz." In the 1940s New York music scene, Mario Bauza, musical director of Machito's orchestra, invited American jazz musicians to sit in with his band of Cuban exiles. Howard McGee on trumpet and Brew Moore on tenor blended in perfectly and set the stage for more famous names like Bird and Diz who rode to prominence on the conjunction of latin rhythms and jazz horns.

Monk's importance to be-bop music is paramount, in fact he invented the term (originally calling it 'Bip-bop'). But unlike Diz (with Chano Pozo), Monk didn't seek out Latin musicians to play with. The only one of his tunes in which I detect a latin beat is 'Bye-Ya' and I think that's as much due to Art Blakey's propulsive drumming as Monk's composition, though Monk's characteristic staggered sense of timing works well with the beat that Blakey is laying down. For this imaginary compilation I've collected Monk tunes performed in a latin style to show how well they adapt to the rhythmic richness of congas, timbales, and other percussion in a latin context. (Hint to Blue Note: release this and it's a sure fire Latin Grammy winner: just give me a name check for thinking of it!)

One aside I have to make about latin music is that the musicians often demonstrate the need to prove their virtuosity in the jazz idiom by quoting as many tunes as possible in a solo. Time and again at latin jazz concerts I have been astounded by sidemen throwing scores of musical thoughts at a riff. It's this riffic virtuosity which makes Monk a natural choice for latin jazz interpretation. His simple themes can be bent in all directions. We sense what Stanley Crouch refers to as "Monk's industrial lyricism" meeting the sussuration of Yoruba percussion (chekeres, bata, clave, etc) and blending in to the rhythmic propulsion for Monk, among all jazz musicians, often seems to approach the ivories like a conga player slapping the skins. When he dances he looks like he's down in the solar, a few rums under his belt, shuffling to the clave like an old rumbero.

THE SELECTIONS

1. Jerry Gonzalez & Fort Apache Band Bye-ya (Rumba Para Monk) 6:42

The set opens with Jerry Gonzalez and his Fort Apache Band from the Latin borough of New York, The Bronx. Their album Rumba para Monk, recorded in 1989, is the first latin album devoted entirely to Monk tunes. The band was inspired by Monk's polyrhythmic sensiblility and I unhesitatingly recommend this (and several of their other albums) to fans of latin jazz. Larry Willis is the pianist. Gonzalez says that "Bye-ya" is a corruption of the Spanish "Vaya!" or "Go!" (an exhortation to jam, as in 'Go, man, go!') He hears a rumba in this: Monk's most latin-influenced tune.

2. Martin Arroyo Quintet Monk Lives (Now is the Time) 2.29

Steve Berrios, the drummer of the Fort Apache band, pops up again on the second track, "Monk Lives," a brief collection of Monk riffs nicely juggled by pianist Martin Arroyo with a less well-known group of Nueva Yorkinos in his quintet.

3. Bongo Logic Straight, No Chaser (Bongo-licious) 3.49

Los Angeles, never lacking in originality, has its own Latin jazz scene, or at least some good local bands. In 1993 Bongo Logic recorded Bongo-licious and included both "Round Midnight" and "Straight, No Chaser." The line-up is a stripped-down charanga (strings and flute instead of brass, as found in a conjunto) but don't expect anything traditional from them.

4. Jerry Gonzalez & Fort Apache Band Jackie-ing (Obatalá) 11.58

It was hard to choose between all the great Monk songs recorded by Jerry Gonzalez so I decided to go with quality rather than limiting his band to one selection. On "Crossroads," the Fort Apache Band plays "Thelingus" a hybrid of Monk and Mingus pieces. If the title sounds vaguely sexual, it's all in your mind. They have a real affinity for the stop-time intro to "Evidence" in the version that appears on their live album Obatalá recorded live in Zurich in 1988 and featuring Milton Cardona on bata and chekere and John Stubblefield on tenor sax. However I opted for the other Monk tune on that album, "Jackie-ing." This later Monk piece is one of his trickiest compositions. Orrin Keepnews relates how at the session on June 4, 1959, Monk showed up without the sheet music of his newly composed piece and offered to show the musicians the changes by playing a bit and humming a bit, but there was a rebellion till Monk went home and found the manuscript. Outstanding here is Papo Vasquez on trombone.

5. Jane Bunnett Epistrophy (Spirits of Havana) 6.57

A faithful rendering of Monk's jagged theme song "Epistrophy" is wrought by Jane Bunnett on soprano and Larry Cramer on trumpet over a really cooking percussion bed (by Grupo Yoruba Andabo) on her Spirits of Havana album. Bunnett is a Canadian who went to Cuba to record this album. Gonzalo Rubalcaba on piano doesn't try anything Monkish but lays down his own Cuban-classical jazz style. Despite the outrageousness of the seemingly perverse chord sequence the tune moves from C#7>D7 to Eb7>E7 and then up to F#mi6 which, in any other hands but Monk's, would seem like a perfectly harmonious set of chords!

6. Bongo Logic Round Midnight (Bongo-licious) 4.37

"Round Midnight" is the most famous of Monk's tunes. It's the one Monk standard in the jazz repertoire and it was hard to choose between the versions. There's an elegant danzon on Rebecca Mauleon's Round Trip album, featuring Orestes Vilató and Jesus Diaz on percussion and John Calloway on flute. However, you can't get enough of a good thing and Bongo Logic demanded an encore.

I suppose if you are going to have the same tune twice it's just as well to run the versions back-to-back for contrast. Named for the famous CuBop suite, 'Manteca,' (written by Diz, Gil Fuller and Chano Pozo) this septet from Rotterdam is led by pianist and arranger Jan Laurens Hartong. They have succeeded in bringing a small salsa revolution to Holland. Their now rare first album, Afrodisia, included a long piece based on several Monk themes, called "Monktuno Suite," (a play on Monk and "montuno") and is worth seeking out.

8. Jerry Gonzalez & Fort Apache Band Ugly Beauty (Rumba Para Monk) 6.33

No, I'm not running out of ideas. I just wanted to include a really sublime ballad ("Ugly Beauty" was a very late Monk composition, dating from 1967), in a fantastic arrangement by Jerry Gonzalez on trumpet and Larry Willis on piano taken from the Rumba Para Monk album.

9. Danilo Perez Bright Mississippi (Panamonk) 5.39

Young Panamanian prodigy Danilo Perez has absorbed the rhythmic lessons of Monk without falling into caricature. A decade after Fort Apache's Rumba Para Monk he issued another jazz album dominated by tunes from the pen of Thelonious Monk. He swings each tune pushing it into the rhythm. Monk wrote "Bright Mississippi" around the changes for "Sweet Georgia Brown." It's easy to see how a standard like "Sweet Georgia Brown" would appeal to Monk. The harmonic resolution (to G) only occurs after three lines (12 bars) of jagged chord clusters in E7th, A7th and D7th. You would expect the resolution to be in A but it drops a full tone to G. Of course the enduring power of the 1920s songbook was something Monk alone seemed to know during the jazz revolution of the 1940s. In an inadvertent nod to Eddie Palmieri, Perez can't stop himself muttering along with the tune!

10. Tito Puente Misterioso (Special Delivery) 4.49

Timbalero Puente was probably the first Latin artist to record Monk tunes. I haven't checked his entire catalogue but he did record "Round Midnight," and, for the Concord label, "Misterioso" in 1996 with Hilton Ruiz on Piano.

This piece of virtuosity is too incredible to leave out: Perez plays "Evidence" with his left hand and "Four in One" with his right. It begs the question, what does he do with his feat? Check it out.

12. New York Ska Jazz Ensemble I mean you (New York Ska Jazz Ensemble) 4.11

One has to end with a bang, and what better way to go out than with a rollicking ska take on "I Mean You"? (Doubtless the only ska interpretation of a Monk tune!) The hyper-talented New York Ska Jazz Ensemble also cover Mingus and Abdullah Ibrahim on their self-titled 1995 album.

[from SHUFFLE BOIL magazine #1, 2001]

THELONIOUS MONK

AFTER HOURS AT MINTON'S (Definitive Records)

The Second World War was a crucial time for jazz as the music evolved from Big Band Swing into more intimate groups featuring extended solos. Within a few years the music would evolve drastically into BeBop (a term coined by Monk). Recorded music at the time was limited to how much would fit on the side of a 10-inch 78 rpm disc, but a clever Columbia University student, Jerry Newman, had two portable disc-cutters and a supply of 12 inch blanks which allowed him to capture ten minute jams at a time. He liked to hang out in Harlem where the scene was swingin' at Minton's Playhouse off 7th Avenue. On any night half a dozen musicians of the calibre of Oran "Hot Lips" Page, Kenny Clarke, Charlie Christian and Roy Eldridge were kicking around some Tin Pan Alley tunes and stretching out. On piano: the one and only Thelonious Monk. THELONIOUS MONK -- AFTER HOURS AT MINTON'S collects a dozen tracks recorded at Minton's Playhouse in May 1941, featuring the legendary pianist. It's a reissue of THE EARLY THELONIOUS MONK on Moon, with the addition of one track "Stompin' at the Savoy" from the recordings made with Charlie Christian. These rare tracks recorded at Minton's in 1941 have appeared in various configurations. The most well-known of them feature Christian, the cool daddy of electric jazz guitar. THE IMMORTAL CHARLIE CHRISTIAN on Laserlight features his Django-inflected runs but I'm always waiting for the band to cool down so I can hear Monk trinkling away. Now the spotlight is on Monk. The sound is not perfect but you can hear it fine as if through a P.A., and almost imagine Monk shuffling his feet and playing his ham-handed version of stride like he's shadow-boxing with the keyboard. Then he'll pull out one of those whole-tone glissandi, light as a feather, and float it by imperceptibly in the background as Joe Guy, with his mute, warbles "I found a million dollar baby... in a five and ten cent store."

On one or two tracks you are almost outside on 118th Street; nearby a couple of kids who have not yet earned the nicknames "Coffin Ed" and "Gravedigger" are playing cops and robbers around the trash cans, hiding down basement stairs. Inside in the smoky room hustlers shuffle, pimps primp, and inter-racial couples sway to the groove. Up on the tiny bandstand Monk is concentrating, sweating in his jacket, tie and hat, his feet seeking invisible organ pedals, sucking in his cheeks in a dramatic reversal of the Dizzy Gillespie look.

After a lugubrious start from Herbie Fields' tenor on "Body and Soul," Roy Eldridge decides to rip it up Kansas City style. "Melancholy Baby" and "Sweet Lorraine" appeared on TRUMPET BATTLE AT MINTON'S where Hot Lips and Joe Guy duke it out. Five of the track appeared on the Xanadu album HARLEM ODYSSEY, but the rest were scattered all over the place. For completists, the set is missing "Topsy" with Hot Lips Page from AFTER HOURS IN HARLEM, and two tracks with Hot Lips Page from SWEETS, LIPS AND LOTS OF JAZZ. It's also missing four tracks with Don Byas that appear on two albums, LIVE AT MINTON'S and MIDNIGHT AT MINTON'S. But this is a concentrated dose of early Monk and the only documentation of his pianistic evolution. The influence of Art Tatum can be heard in strident backing runs on "Sweet Lorraine" but Monk is definitely audible in his own inimitable style, especially on "My Melancholy Baby," which has a screaming outro that is far from melancholy. The implacable Monk remains calm when Herbie Fields starts grandstanding on tenor and keeps soloing even after Hot Lips returns on trumpet. Things look about to fall apart but Monk calmly leads the way, solo, into the bridge and brings about a resolution. It's a lesson in diplomacy. For "You're a Lucky Guy" Monk is at his most relaxed, the piano is very audible (Newman must have been sitting closer to it that night), and you can clearly hear audience chatter and the exhortation of the band members as the three trumpeters and the unknown tenor saxophonist swing it.

In December 1941, the USA entered the war and many musicians were called up. After then Monk only worked sporadically, but notably with Coleman Hawkins with whom he recorded four sides in October 1944. He continued to play at Minton's till 1948 and the beginning of his official recording career came in October 1947.

THELONIOUS MONK

THE COLUMBIA YEARS / '62-'68

For years now, Columbia has been reissuing their Monk catalog with "newly discovered" out-takes to pep up the sales. STRAIGHT, NO CHASER added brilliant new cuts of "Green Chimneys" and "I didn't know about you" and restored three tracks to their original length. The latest triple-decker, THELONIOUS MONK / THE COLUMBIA YEARS / '62-'68 includes six previously unreleased alternate takes and three tracks restored to their full length (with bass and drum solos). It's a scrappy compilation and lacks the cohesion of the single albums, but for a die-hard Monk fan it's a major treat. But be warned: the packaging sucks. The booklet is illegibly and illogically typeset and the CDs fall out of the cardboard case because the sponge rubber nipples aren't strong enough to hold them in place. These design flaws are typical of Columbia who are clueless when it comes to making CD packages. Columbia hired rival producer Orrin Keepnews (who oversaw Monk's tenure at Riverside) to produce the reissues. His son, Peter, writes an apologetic letter asking why no one respects Monk's Columbia years. Was it because Monk had locked down his partnership with Rouse and also fixed his repertoire, so his albums from that period lack the "try anything" approach of many of his Riverside albums?

It may be that Columbia kept trying to team him up with their other artists, put him on tour with ill-rehearsed big bands and also asked him to record the Lennon-McCartney songbook, or add an electric guitar to his line-up. That would be enough to make anyone despise the label. His last quartet album for Columbia, UNDERGROUND, contained all new material however.

"Thelonious" appears here in an alternate take, and "Ugly Beauty" for the first time in its complete form. "Underground" won a Grammy, but not for the music -- for the cover design. Though Monk was at the peak of his popularity in the mid-sixties (with a cover story in TIME magazine) the label treated him shoddily. One of the biggest frustrations is apparent in the film STRAIGHT, NO CHASER: the band is coasting through a beautiful version of "Ugly Beauty" when Teo Macero comes over the intercom: "Monk, now let's really do one, alright?" Monk replies: "What did you stop us for? Shit. Where was we at before we were so rudely interrupted?" They resume, then at the end Macero asks again "Wanna try one?" "I'd like to hear how that sounds," replies Monk. "Let's take one, then I'll play it back for you," says Macero. "Why is it nobody wants to do what I ask them to do?" says Monk in obvious frustration. "Rehearse a bit." says Macero. "You rehearse every time you play on an instrument," replies Monk. Tape is cheap. Who knows why Macero was riding the pause button.

If you have not been keeping up with the various Columbia album reissues, now's your chance to get the rare stuff to add to your collection. It's all good, of course. As Monk said, "There are no wrong notes." Charlie Rouse more ruefully noted that Monk liked to do things in one take, so there was no chance to really work it out in the studio: "Once you play it the first time that's when the feeling starts going downhill." But by the time the songs got into the repertoire and the band played them night after night, Rouse showed what he could do.

The first CD is the studio stuff. There are a few previously unreleased tracks, "Think of One," "Pannonica," "Honeysuckle Rose" and "Thelonious." "Thelonious" is one of his toughest pieces. Like a one-note samba, it's all in the feeling and the rhythm. The right hand plays B flat (occasionally adding the octave), while the left hand walks down in sevenths. Nothing to it, yet it's catchy.

The second CD is the heart of the matter, lots of solo piano (a must-have if you didn't get MONK ALONE), and five previously unissued tracks, though the big band sets are my least favourite of his recordings. Most intriguing here is the solo version of "Don't Blame Me" recorded in Puebla, Mexico, in May 1967. Where's the rest of this gig? Maybe that was on the Brubeck tour Columbia set up for the duo.

Disc Three consists of live gigs, mostly with the quartet. Aficionados will have the reissues of the LIVE AT THE IT CLUB and LIVE AT THE JAZZ WORKSHOP sets as they are the fullest account of his classic quartet from the mid-sixties with Charlie Rouse on sax, and straight-men Larry Gales on bass and Ben Riley on drums. Rouse is an under-rated tenor player. He got around the complexities of Monk's compositions and throws himself into them with a fresh vigor each time, though they played the same songs night after night. "Well, You Needn't" from the It Club is one of the tightest Monk recordings ever. That inspired album also contains my favourite version of "Round Midnight."

Included here is "Nutty" -- the outstanding track from the MILES & MONK AT NEWPORT set. Actually Miles & Monk didn't appear together: the two sets were recorded five years apart! But for the only time Pee Wee Russell sat in with Monk and his is an eccentric genius parallel to that of Monk. Too bad they didn't get to jam more or do studio dates. As it is, Pee Wee Russell's clarinet comes in obliquely against the solid four-four of the rhythm section. Monk always told guest hornmen to make the drummer sound good. He comps handsomely and you have to wonder what would happen if everyone had dropped out leaving them alone to play a duet. Russell was one of an older generation, used to playing Dixieland with Jack Teagarden or Bix Beiderbecke. This was quite a different setting and even though it was unrehearsed his part adds an eerie and complementary tone to the proceedings.

When I saw Monk at Shelly's Mannehole in LA in 1971 his quartet were gone. I've no idea who was on the bandstand. Monk himself had just got out of hospital and was trying his hardest to be present though he spent most of the set at the side of the bandstand watching, not dancing. They kicked us out after the first set. On the way home we had a tire blow-out at 90 mph on the Ventura freeway. It was a night to forget.

[from SHUFFLE BOIL magazine #2, Summer 2002]

THELONIOUS MONK QUARTET

MONK ROUND THE WORLD (TMF 9325)

The shot heard round the world was fired in Sarajevo and started a war. The note heard round the world was a minor second played by Thelonious Monk, Cootie Williams and others and started a revolution. Be-bop is now old-time jazz though it was an outrage sixty years ago, and it's still weird when you hear Monk playing "Epistrophy" that goes from C#7 to D7 over and over, then up a tone to Eflat7 to E7, and when you get sick of that it starts over. There's sort of a resolution in F# minor 6th, or is it B7 (as Monk might say, "pick one") but nothing you would call a tune, it's more like interlude music, or silent movie music indicating "the train's a-rolling!" Monk opened and closed every show with it and recorded it two dozen times. It's an enigma wrapped in a questionaire. But you can't tell if his statements are questions or answers. Monk is still difficult, after sixty years, but you can't deny he swings. There's Charlie Rouse, Tonto to Monk's Lone Ranger, acting like this was always meant to be thus, breathing lyrically as earnest bass and drums keep things metrical. But then there's Monk: is he drunk? what went clunk? He looks like a great bear woken from hibernation, sweating in his overcoat, can't seem to sit straight at the piano, then --whunk-- he adds a "grace note" with his elbow. The drummer inverts the rhythm and starts a loping shuffle. Monk stops and adjusts his signet ring, the appreciative Parisians burst into applause. At what? A living legend they "get" more than unsophisticated Americans. Or is it his theatrical presence? (I once went to a John Cage concert in London in 1968 where the pianist played the inside of the grand piano with a matchbox. Was it the Emperor's New Clothes syndrome that caused us to give him a standing ovation?) In the early sixties, Monk took a quartet on tour of Europe annually. He played the same songs -- his own -- over and over, once in a while throwing in "April in Paris" or "Body and Soul" so folks would get a sense of where he was coming from. His American labels weren't happy with this: They wanted new stuff, or failing that, a set of Beatles covers. He wasn't prolific but content to find more things to say within "Ruby My Dear," "Bemsha Swing" or "Hackensack." Then some nights he would call for a set of standards, like that cold night in Paris in November 1967 when the set list was "Sweetheart of all my dreams" (Consistently mislabelled "[Just one way to say] I love you"), "Lulu's back in town," "Just a gigolo," "Sweet and lovely," and "I'm getting sentimental over you." What corn; what genius!

Here's another reissue of Monk playing his own tunes, and it's a great set. Sort of a hypothetical ideal Monk gig. Other than the obligatory opening and closing bits of "Epistrophy" there are five well-chosen tunes, worked out by Rouse, three different bassists and two different drummers, but they are all well-trained to their parts and you won't notice. It's a syncretic whole. I thought I had all of Monk's filmed appearances on video, but here's a 27-minute DVD of the March 1965 London gig that sports two more of his tunes, recorded at the Marquee Club on a night when the Who and Yardbirds must have been out of town. Thelonious Records has also issued the Paris Olympia set with bonus DVD. As I have it on vinyl and CD (from Charly Records in UK 1994), I'll pass, but it was a legendary night. I suppose their master plan is to eke out more bits and pieces with whatever rarities they can possibly find and keep the diehards like yours truly coming back for more.