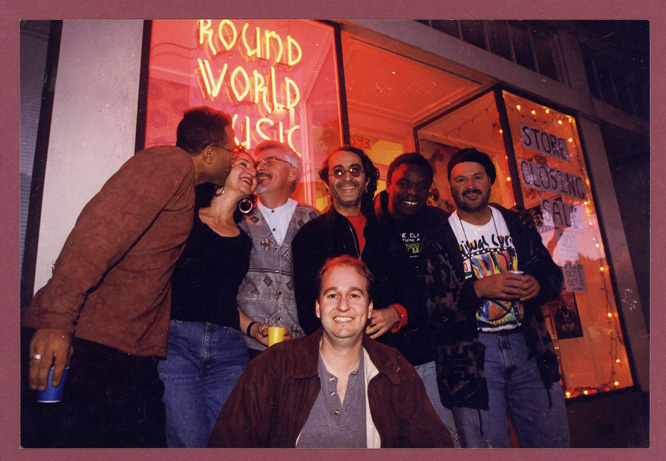

The Round World Music crew: L to R: Ian de Silva, Laura "Lulu" Yanow, yours truly, Serge El Baz, Joe Wanzala, Greg Landau; down in front: Roberto Leaver

IJ & AJ, goofing with Serge and Khaled at KUSF

Cheb i Sabbah listening party

Cheb i Sabbah In Memoriam

In November we lost Cheb i Sabbah, a bright light in the world music DJ booth. I knew Serge for 30 years and found him to be warm and witty, honest and straightforward, and only slightly befuddled by the cloud of hashish which encircled his head at all times like a halo. He was born Haim Serge el Baz in Constantine, Algeria in 1947. His parents were Jewish and, having received French passports, moved to Paris before the revolution. It was in France that Serge spent his teenage years, becoming a fan of American soul music. He moved to New York where he joined the Living Theatre, the experimental troupe founded by Julian Beck and Judith Malina. I was never so scared as when I attended the Living Theatre performance of Frankenstein at the Roundhouse in London in 1968. I was petrified when they started dragging audience members out, screaming and kicking. In New York Serge met Don Cherry the jazz trumpeter and made his first album, The Majoun Traveller, with overdubs of Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry on some Gnawa music, and including snippets of Beat poet Ira Cohen's reading. He also befriended the German actor Klaus Kinski and when Serge moved to San Francisco, Kinski was living in Marin. He remarked once that suddenly there was heavy security, guys in shades with earpieces, which freaked him out, until he discovered Kinski's daughter Nastassia was in town and her entourage required the beefed-up security because of stalkers and paparazzi.

I met Serge when he came to work at Round World Music, the happy haven of world music aficionados started by Robert Leaver and Fred Hill in the Mission district in 1984. With his horn-rims, stubbly beard and thick accent, Serge reminded me of Peter Sellers playing a Russian spy. He also had a twinkle in his eye at all times. A quirk of speech was the way he said, "You know what I'm saying?" at the end of sentences, but the way he said it, it sounded like "You know I'm insane?" He began deejaying at Nickie's Barbeque and Bar on Haight Street and soon had a devoted following for his Tuesday night North African trance dance sessions, which he saw as therapy for his followers. I have no respect for DeeJays: it takes little talent to spin records, but Serge began to explore the new technology that would allow him to loop rhythms and change tempo to synch disparate elements. It was not techno in the sense of driving beats with a few musical clips but rather an organic whole that would move in and out of moods and he had the dance-floor in the palm of his hand. Don Cherry would hang out at the store, looking for Malian cassettes, and sit in with some of the acts Serge brought to town.

Suzanne, Serge's wife, was tall and waspish, seemingly very "straight," and a classic demonstration of the "opposites attract" syndrome. They had met in Paris in 1968, the year of student riots. They had two kids, Eva who wanted to be a model, and a son, Elijah, who took the stage name Opium and followed his dad into music.

To supplement his income Serge dealt hash (after all his namesake Hassan i Sabbah, the "Old Man of the Mountain," was the founder of the Hashishim cult). I gave up recreational drugs many years ago when hybrids appeared that made you catatonic from one toke, but an out-of-town friend wanted to score and so we visited El Baz in his lair. While he was in the other room measuring the deal, we looked around. He had no furniture, we sat on the carpet; his walls were covered in Indian hangings and posters of Hindu deities. Suddenly we noticed little piles of cash all over the rug. He had sorted out stacks of money like a kid playing Monopoly! But soon after he suffered a blow: two men dressed as UPS delivery men showed up at his door with a package, pistol-whipped him, tied him up and cleaned out his stash and his cash.

We thought he had retired from this dangerous game but then, when Robert was in Cuba, he stashed a lot of marijuana in the store room at Round World. Late one Friday night I got a phone call from the police saying the alarm was ringing at Round World. Robert's number didn't answer (as he was in Cuba) and Serge was out deejaying; apparently mine was the third number on the alarm company contact list. I drove over there to find two cops with flashlights outside. I opened the door and turned off the alarm. A window in the store room had been left ajar and wind had caused something to fall, tripping the motion detector. The cops sniffed the air, catching the pungent odor and looked around. I gestured at the window with a "What can you do in this neighborhood?" look on my face, and turned off the light.

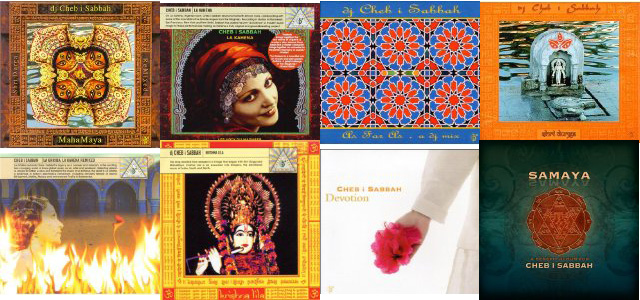

Serge regularly brought acts to town and often to my radio show for promotion, so I met Cheb Mami, Cheba Fadela, Cheb Khaled and Hakim and got to see them in concert. The first Khaled and Hakim concert had been canceled because of the September 11 bombings in New York, so was rescheduled a year later. The crowd went wild, jumping on the seats of the Berkeley Community Theatre, yelling and waving huge flags of the Arab nations. Serge came on stage to ask the crowd to calm down, saying we don't want the fire marshals to shut it down. It was a riot of joy. His biggest coup was the first American tour of the great Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan for which we, his Round World posse, were the ushers and got front row seats. But his great passion was his music and he began to travel to India to record performers for the kinds of sounds he wanted to use in his discs.

He issued 7 CDs through Six Degrees Records in San Francisco. They were immensely popular, even influential on deejay culture in general. His songs were remixed by Bally Sagoo and Transglobal Underground among others. He became a celebrity and would be flown across continents to deejay one night at a private party. But it didn't go to his head: he would put the same effort into his weekly gigs in little clubs in SF as for opening for big acts. I ran into him a couple of years ago on Telegraph Avenue. He didn't look well, but laughed it off. Soon after he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. All the smoking got to him. He had no insurance and he was given a month to live, but instead of giving up, he flew to Germany for treatment and then went back to India to make peace with the gods. He survived another two years and got to feel the outpouring of love and affection his legions of fans had for him, crowd-sourcing to pay his medical bills and attending benefit concerts. Not everyone gets to go out knowing how they will be remembered, but he knew he was adored and his musical legacy will continue to comfort us.